Cumulative reductions in Blosc2

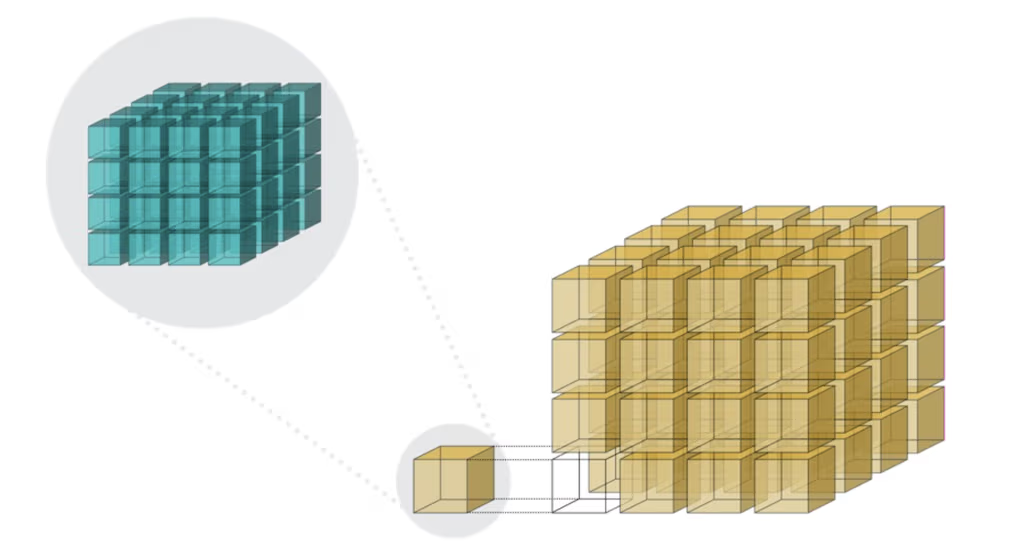

As mentioned in previous blog posts (see this blog) the maintainers of python-blosc2 are going all-in on Array API integration. This means adding new functions to bring the library up to the standard. Of course, integrating a given function may be more or less difficult for a given library which aspires to compatibility, depending on legacy code, design principles, and the overarching philosophy of the package. Since python-blosc2 uses chunked arrays, handling reductions and mapping between local chunk- and global array-indexing can be tricky.

Cumulative reductions

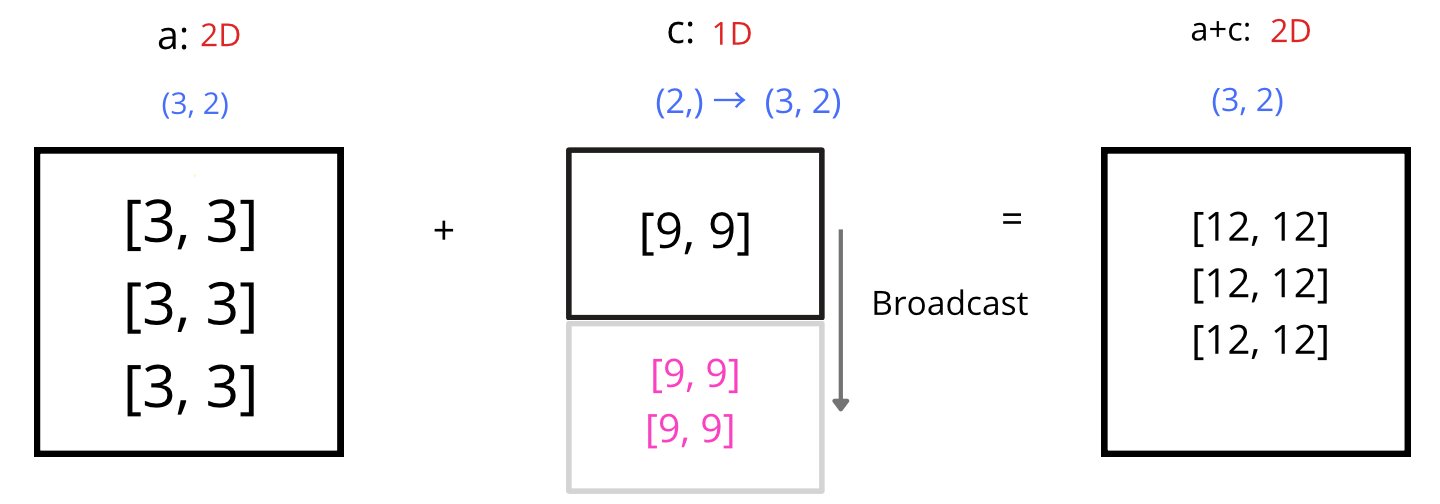

Consider an array a of shape (1000, 2000, 3000) and data type float64 (more on numerical precision later). The result of sum(a, axis=0) would be (20, 30) and sum(a, axis=1) would be (1000, 3000). In general we can say that reductions reduce the sizes of arrays. On the other hand, cumulative reductions store the intermediate reduction results along the reduction axis, so that the shape of the result is always the same as that of the input array: cumulative_sum(a, axis=ax) is always (1000, 2000, 3000) for any (valid) value of ax.

This has a couple of consequences. One is that memory consumption may be rather important: the array a will occupy math.prod((1000, 2000, 3000))*8/(1024**3) = 44.7GB, but its sum along the first axis only .0447GB. Thus we can easily store the final result in memory. Not so for the result of cumulative_sum which also occupies 44.7GB!

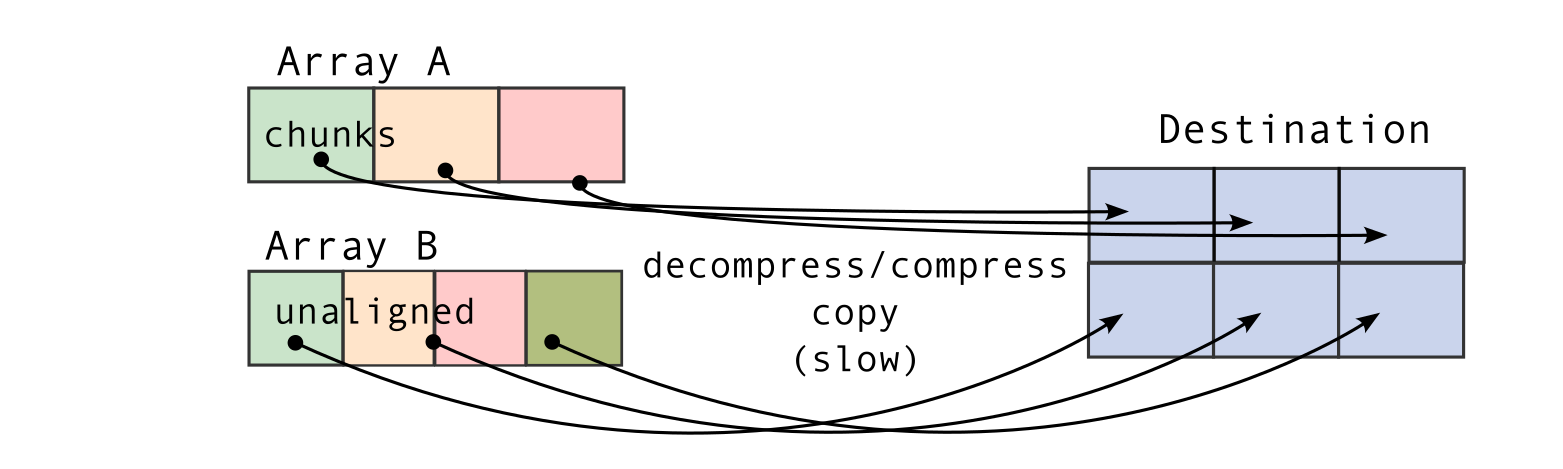

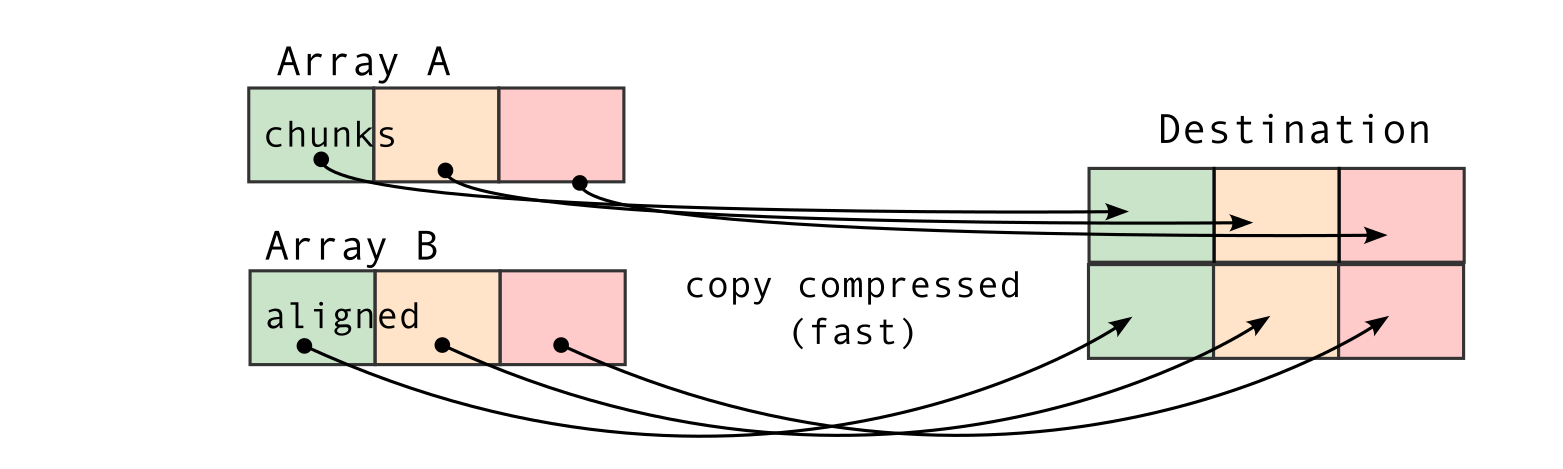

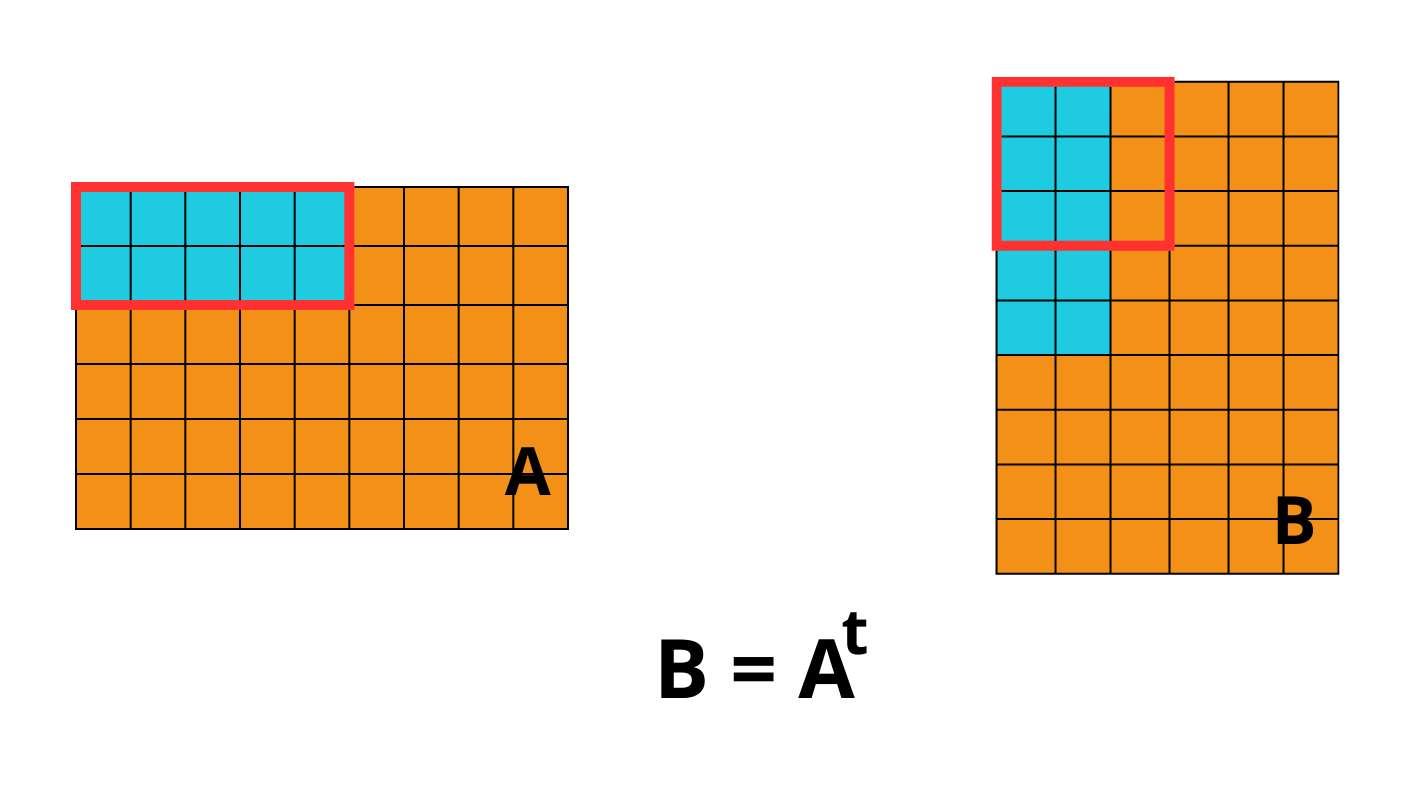

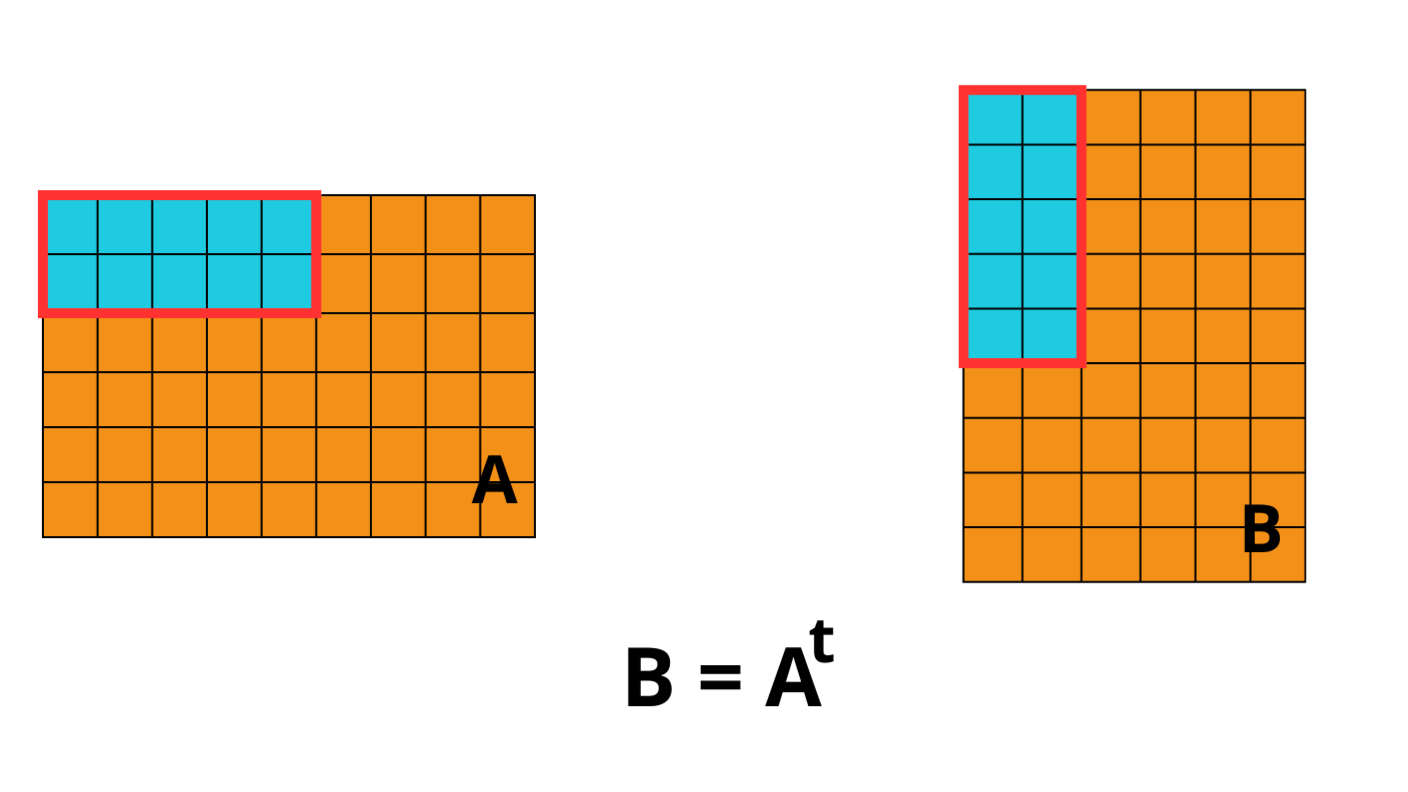

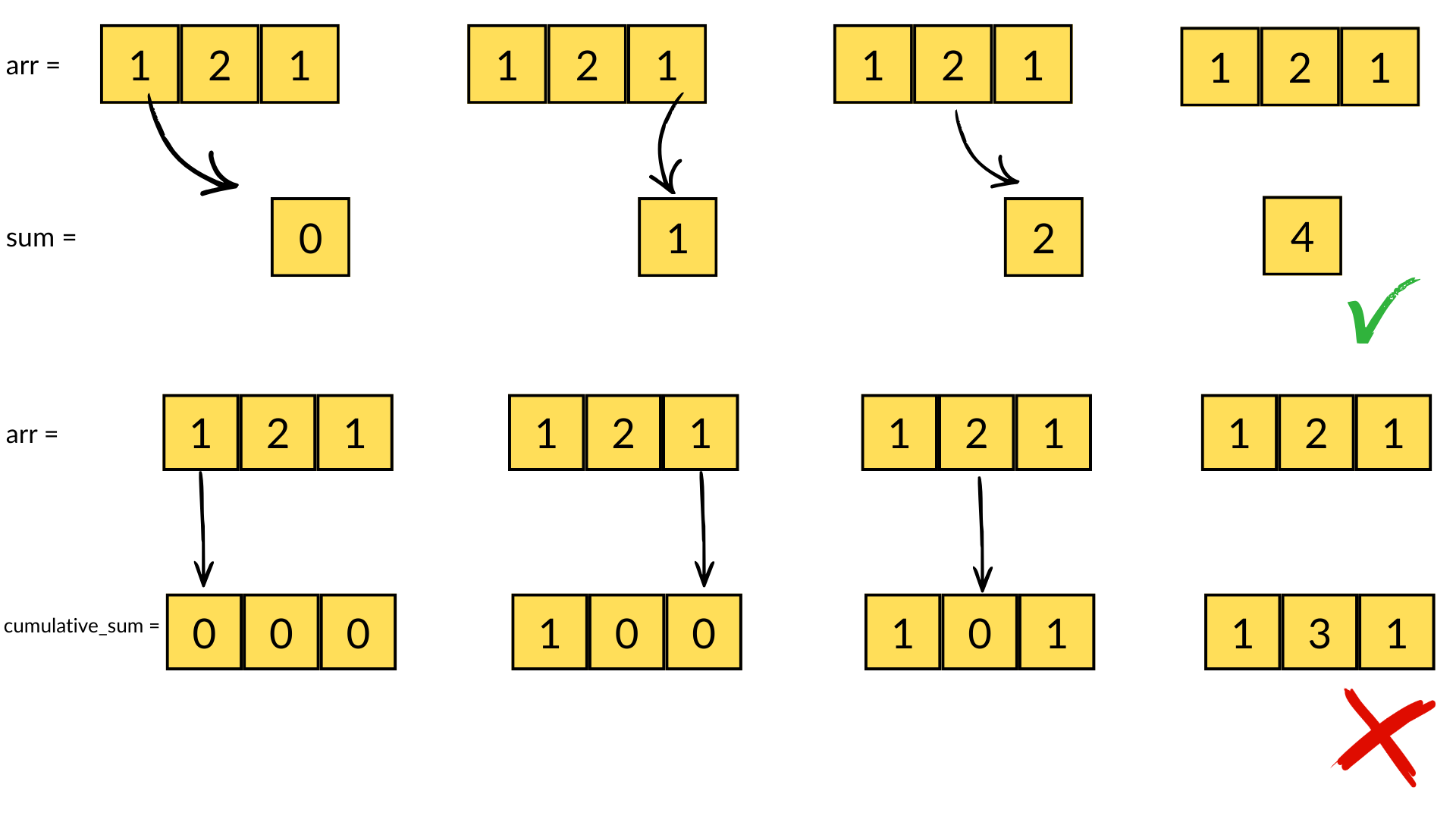

The second consequence, for chunked array libraries, is that the order in which one loads chunks and calculates the result matters. Consider the following diagram, where we have a 1D array of three elements. To calculate the final sum, we may load the chunks in any order and do not require access to any previous value except the running total - loading the first, third and finally second chunks, we obtain the correct sum of 4. However, for the cumulative sum, each element of the result depends on the previous element (and from there the sum of all prior elements of the array). Consequently, we must ensure we load the chunks according to their order in memory - if not, we will end up with an incorrect final result. A minimal criterion is that the final element of the cumulative sum should be the same as the sum, which is not the case here!

Consequences for numerical precision

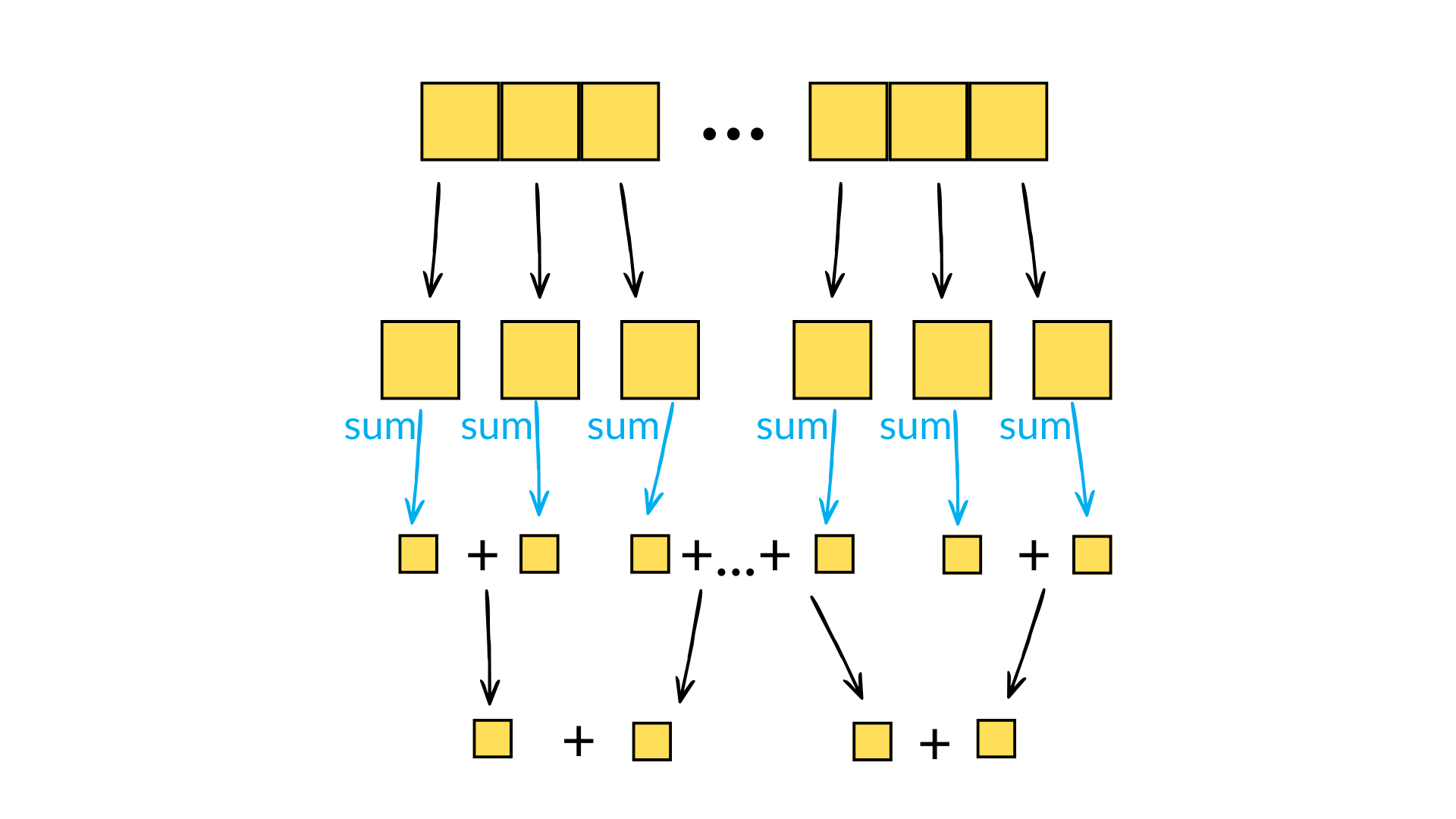

When calculating reductions, numerical precision is a common hiccup. For products, one can quickly overflow the data type - the product of arange(1, 14) already overflows the maximum value of int32. For sums, rounding errors incurred due to adding elements of a small size to the running total of a large size can quickly become significant. For this reason, Numpy will try to use pairwise summation to calculate sum(a) - this involves breaking the array into small parts, calculating the sum on each small part (i.e. simply successively adding elements to a running total), and then recursively summing pairs of sums until the final result is reached. Each recursive sum operation thus involves the sum of two numbers of similar size, thus reducing the rounding errors incurred when summing disparate numbers. This algorithm also only has a minimal additional overhead compared to the naive approach and is eminently parallelisable. And it has a natural recursive implementation, something which computer scientists always find appealing even if only for aesthetic reasons!

Unfortunately, such an approach is not possible for cumulative sums since, as discussed above, order matters! One possibility is to use Kahan summation (the Wikipedia article is excellent), which does have additional costs (both in terms of FLOPS and memory consumption) although these are not prohibitive. One essentially keeps track of the rounding errors incurred with an auxiliary running total and uses this to correct the sum:

# Kahan summation algorithm tot = 0 tracker = 0 for el in array: corrected_el = el - c # nudge el with accumulated lost digits temp = tot + corrected_el # lose last few digits of el tracker = (temp - tot) - corrected_el # store the lost digits of el tot = temp

In implementation, we calculate the cumulative sum on a decompressed chunk in order and then carry forward the last element of the cumulative sum (i.e. the sum of the whole chunk) to the next chunk, incrementing the result of the cumulative sum by this carried-over value to give the global cumulative sum. Thus, we can use Kahan summation between the small(er) values of the local chunk cumulative sum and the large(r) carried-forward running total to try and conserve precision.

Unfortunately, we still observe discrepancies with respect to the Numpy implementation (which sums element-by-element essentially) of cumulative sum - but this also differs from the results of np.sum due to the latter's use of pairwise summation! Finite arithmetic imposes an insuperable barrier: three different algorithms cannot guarantee agreement in every possible case. Since the Kahan sum approach has a slight overhead, we decided to junk it, as it did not improve precision sufficiently to justify its use.

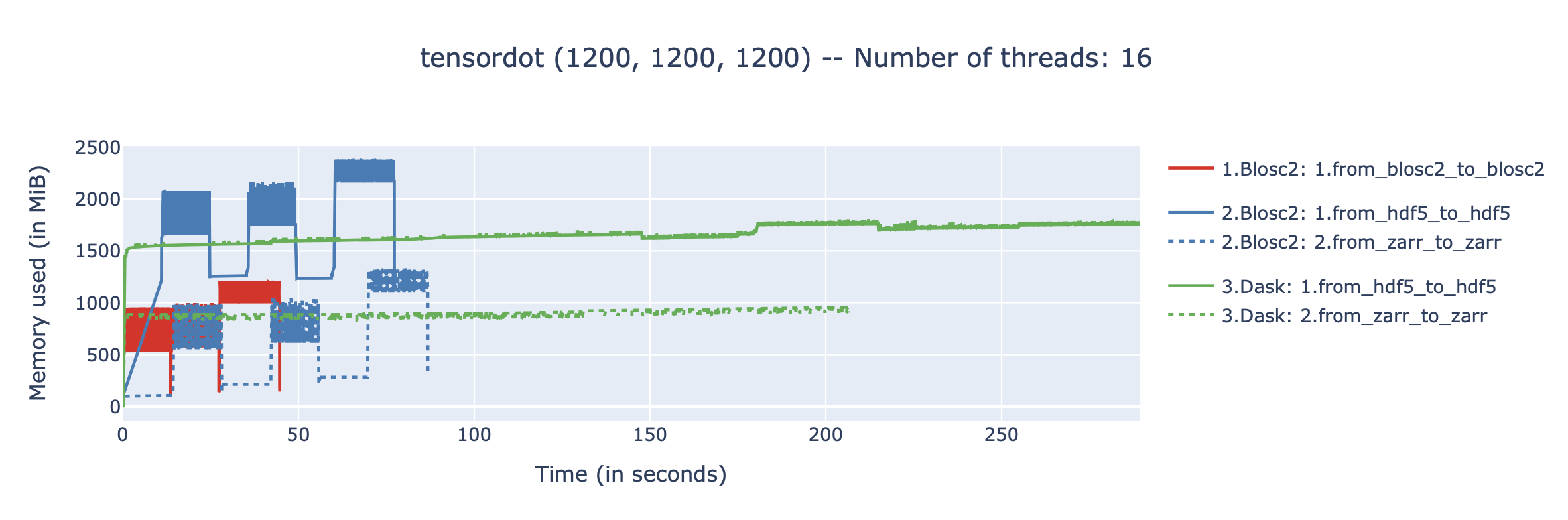

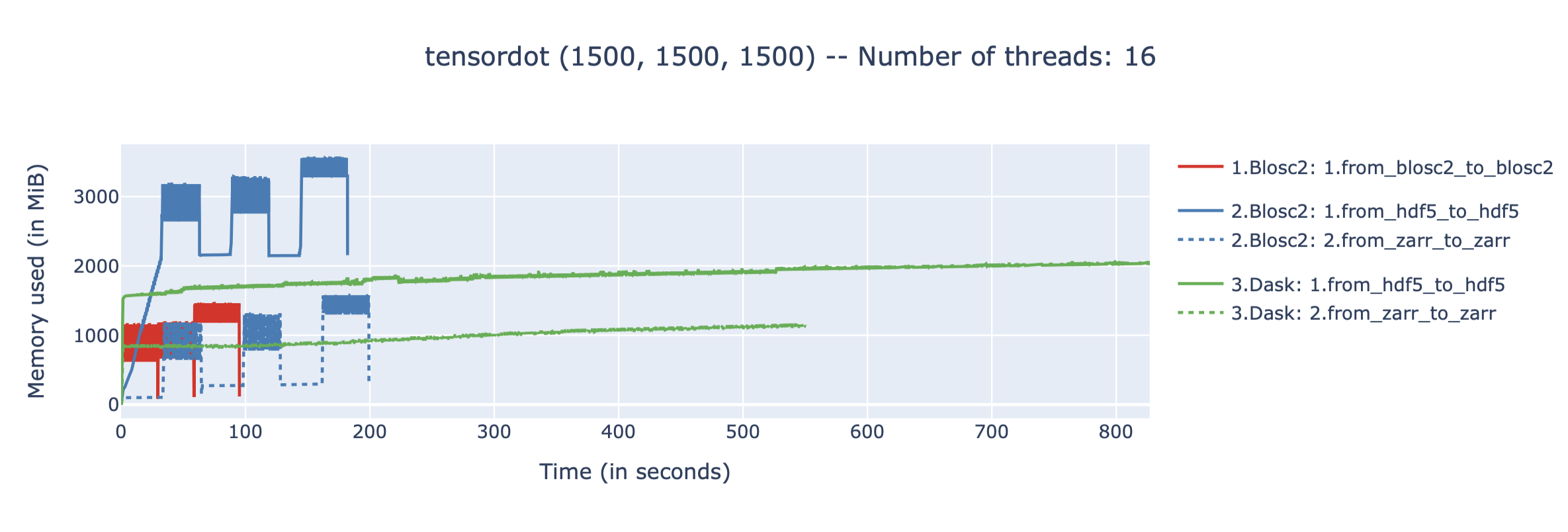

Experiments

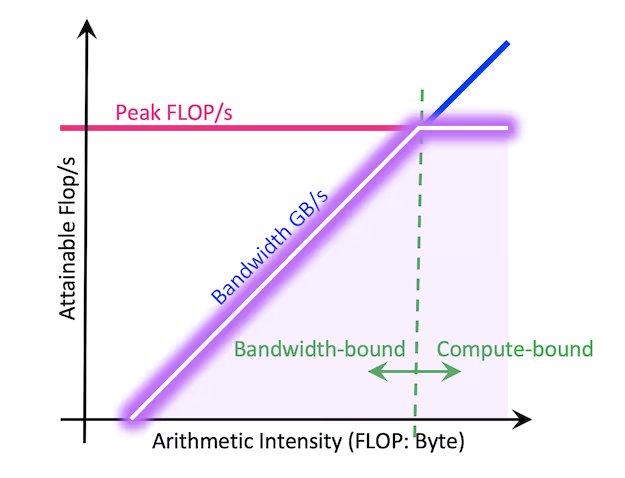

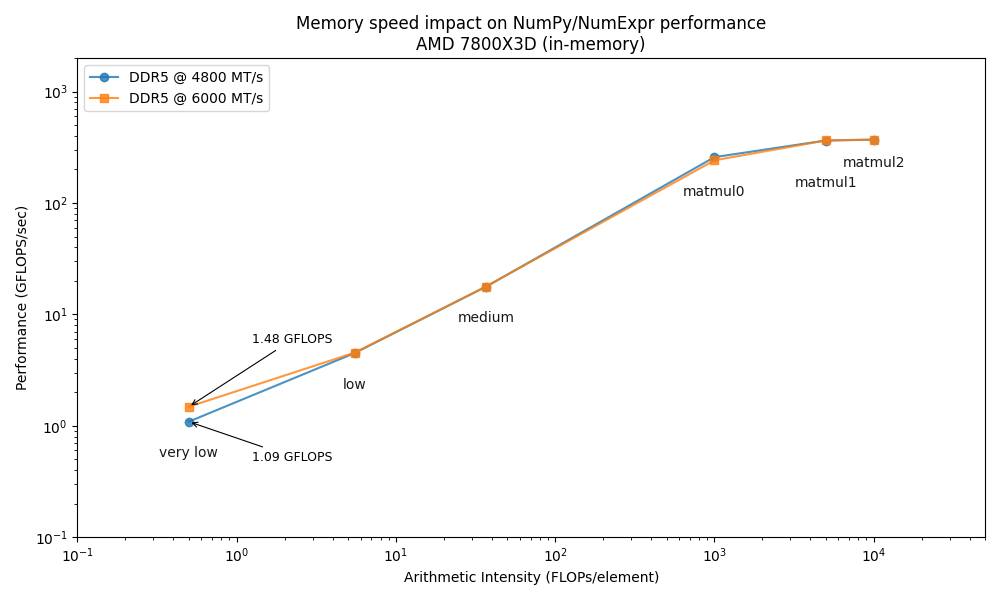

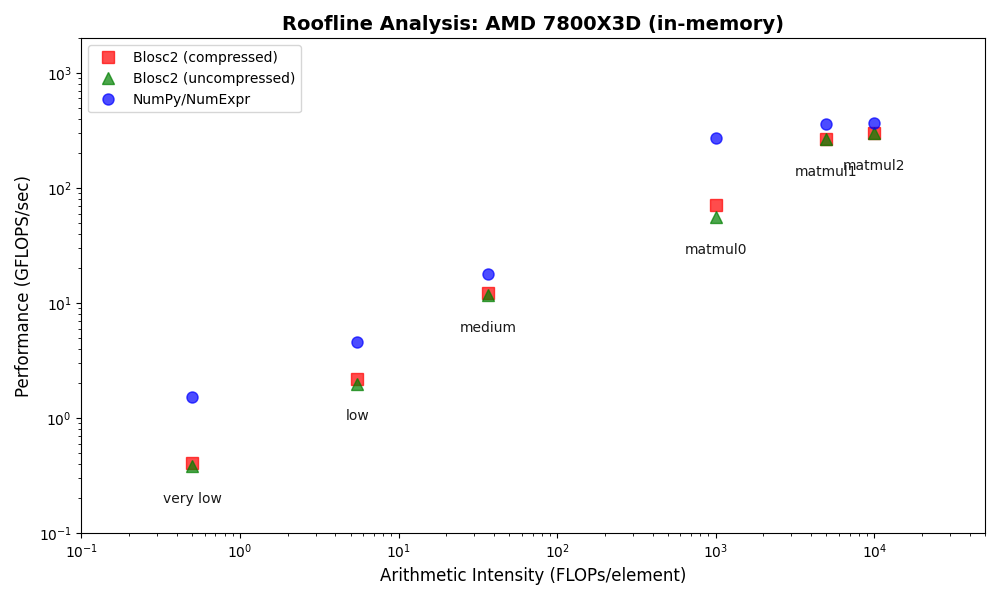

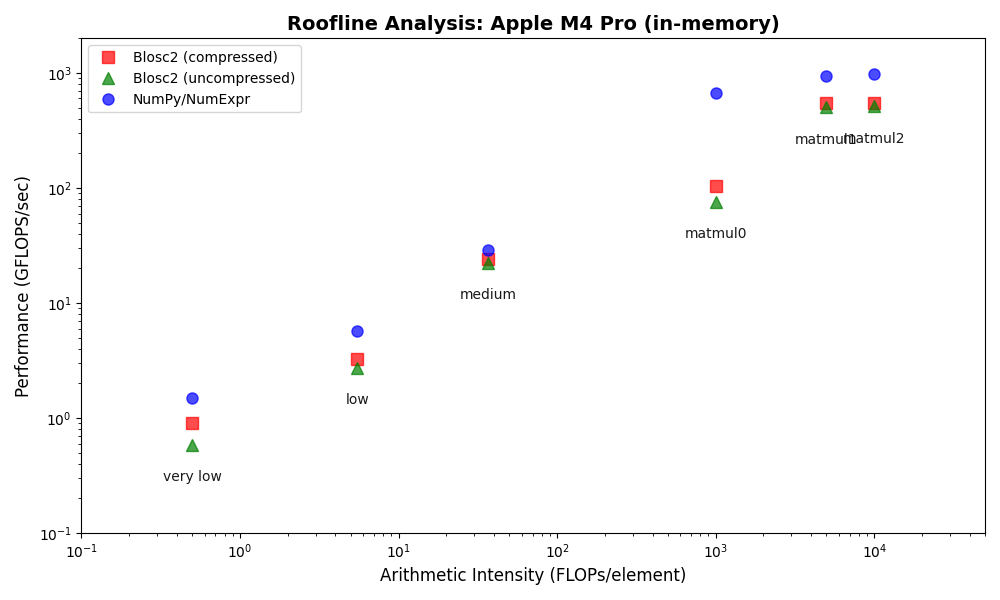

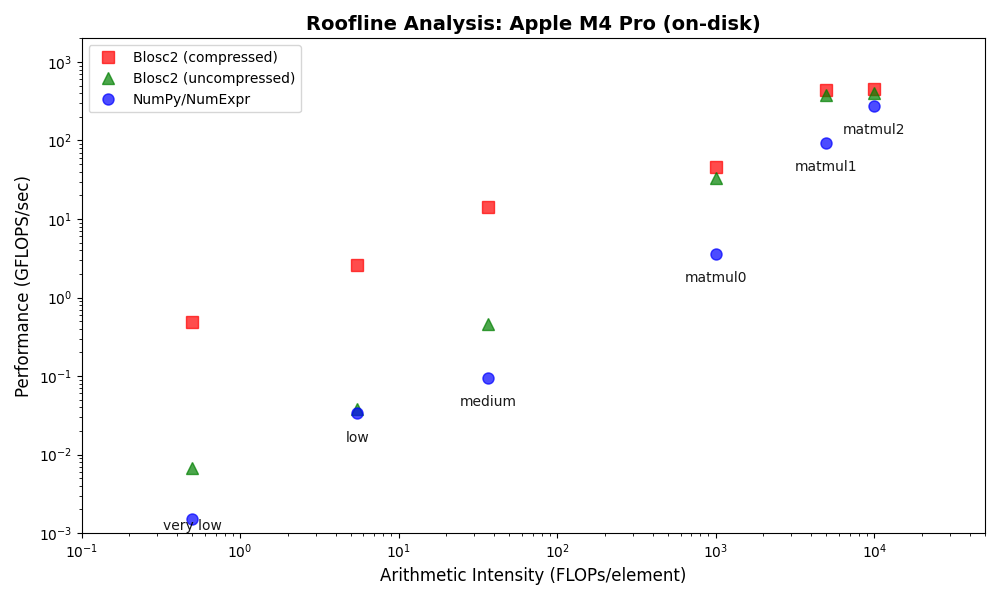

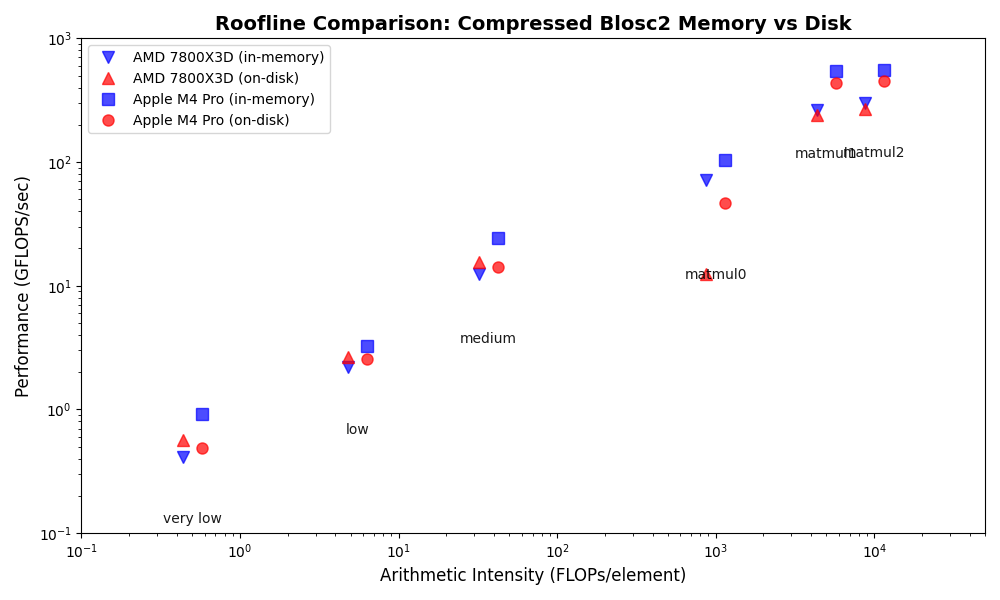

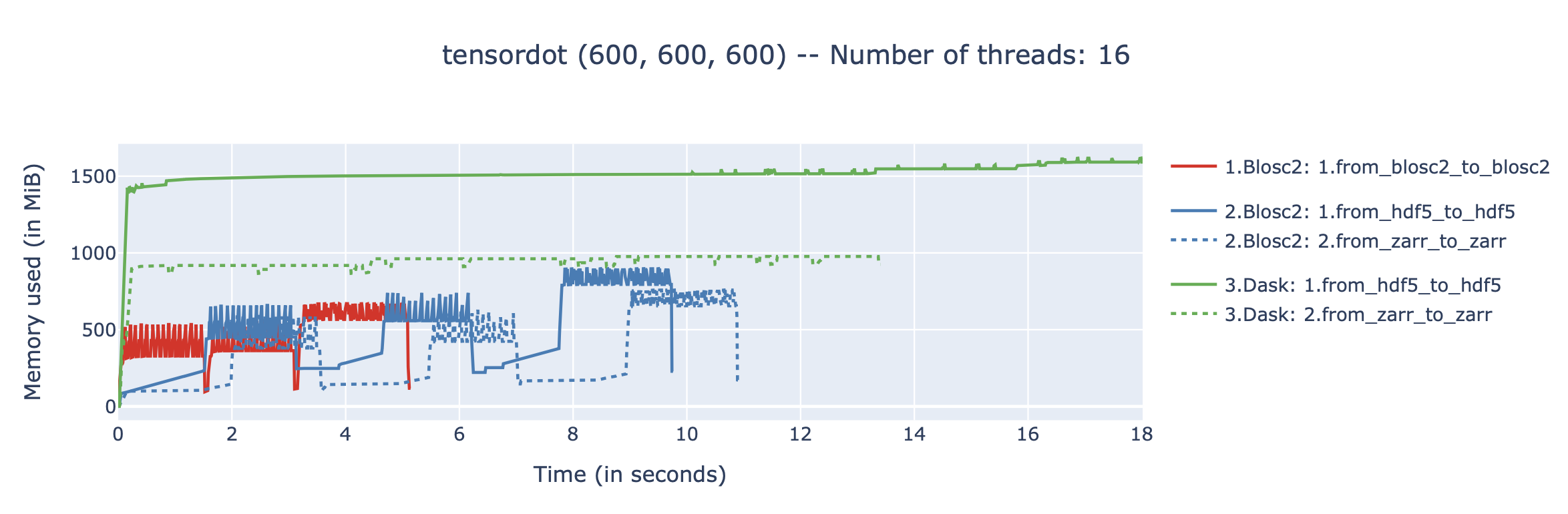

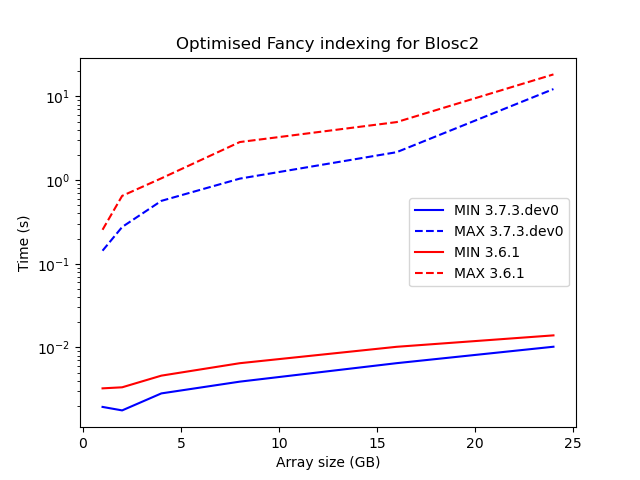

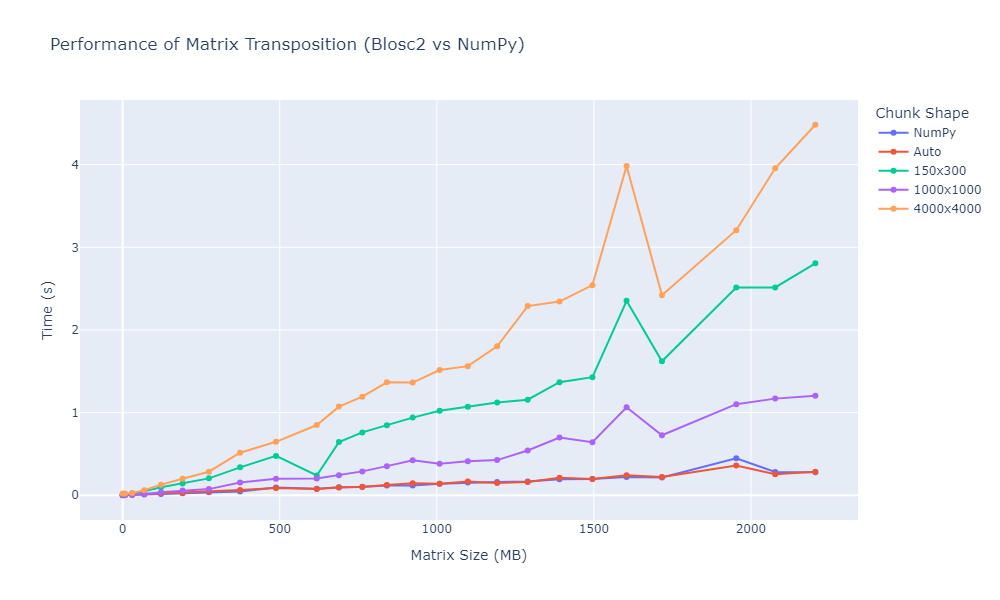

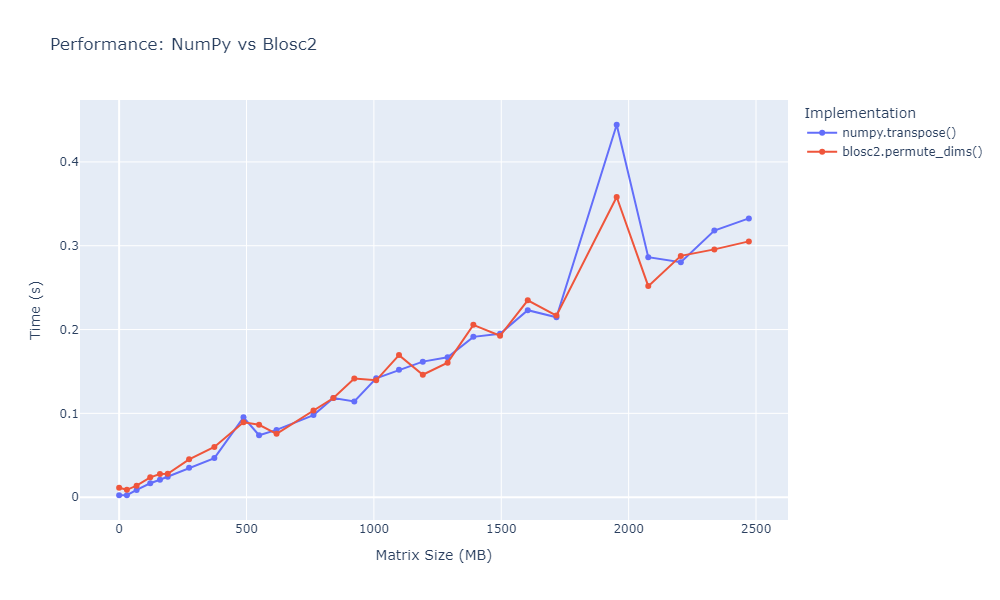

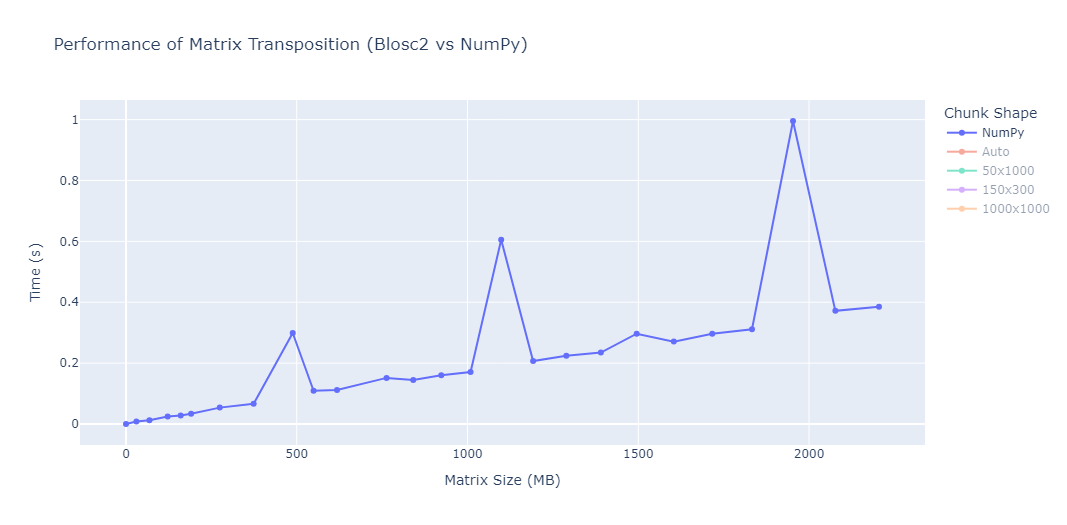

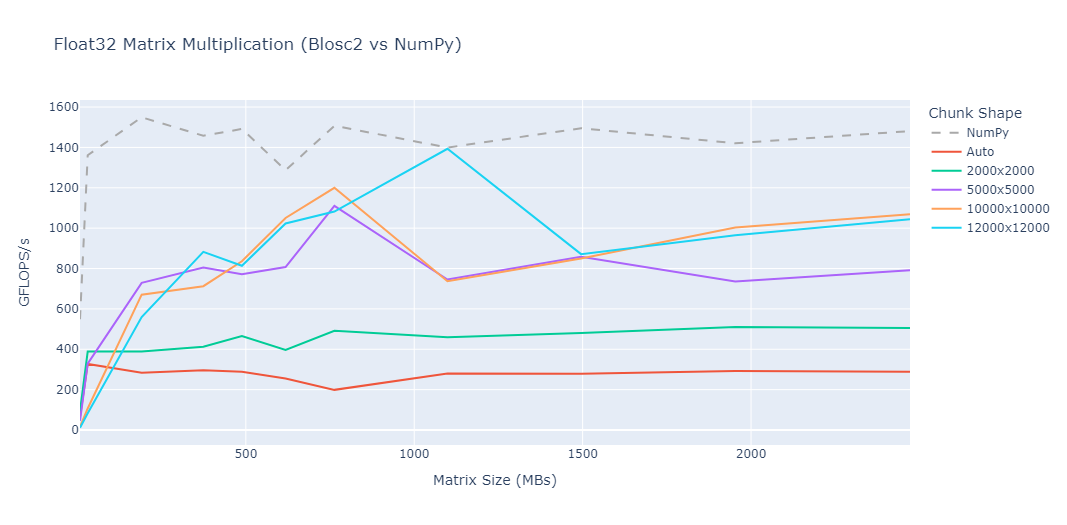

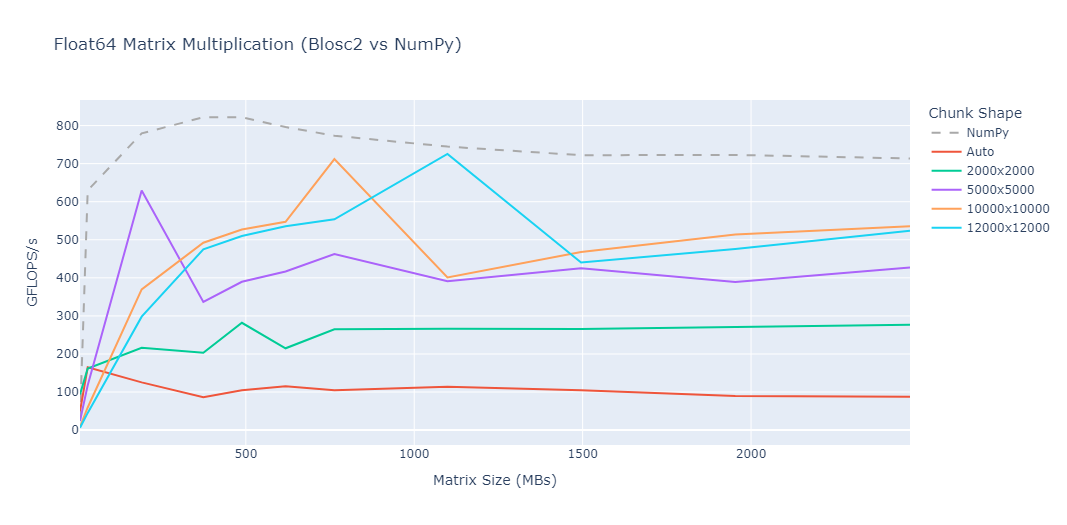

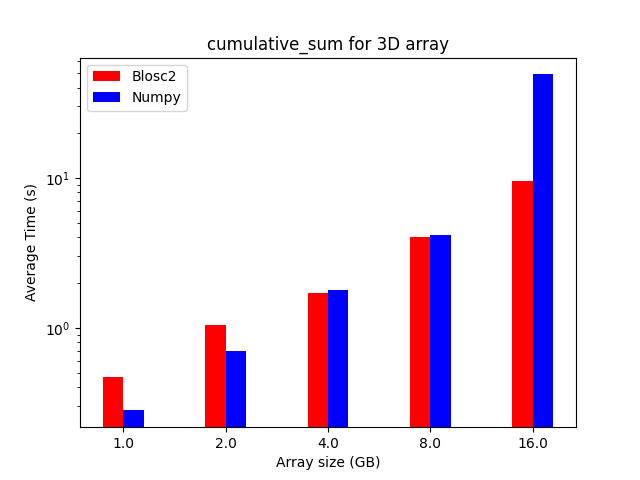

We performed some experiments comparing the new blosc2.cumulative_sum function to Numpy's version for some large arrays of (of size (N, N, N) for various values of N). Since the working set is double the size of the input array (input + output), we expect to see significant benefits from Blosc2 compression and exploitation of caching. Indeed, once the working set size starts to approach the available RAM (32 GB), NumPy begins to slow down rapidly and when the working set exceeds memory and swap must be used NumPy becomes vastly slower.

The plot shows the average computation time for cumulative_sum over the three different axes of the input array. The benchmark code may be found here.

Conclusions

Blosc2 achieves superior compression and enables computation on larger datasets by tightly integrating compression and computation and interleaving I/O and computation. The returns on such an approach are clear in an era of increasingly expensive RAM and thus increasingly desirable memory efficiency. As an array library catering in a unique way to this growing need, bringing Blosc2 into greater alignment with the interlibrary array API standard is of utmost importance to ease its integration into users' workflows and applications. We are thus especially pleased that the performance of the freshly-implemented cumulative reduction operations mandated by the Array API standard only underline the validity of chunkwise operations.

The Blosc team isn't resting on our laurels either, as we continue to optimise the existing framework to accelerate computations further. The recent introduction of the miniexpr library into the backend is the capstone to these efforts, and has made the compression/computation integration truly seamless, bringing incredible speedups for memory-bound computations, justifying Blosc2's compression-first, cache-aware philosophy. This all allows Blosc2 to handle significantly larger working sets than other solutions, delivering high performance for both in-memory and on-disk datasets, even exceeding available RAM.

If you find our work useful and valuable, we would be grateful if you could support us by making a donation. Your contribution will help us continue to develop and improve Blosc packages, making them more accessible and useful for everyone. Our team is committed to creating high-quality and efficient software, and your support will help us to achieve this goal.